The U.S. Supreme Court has overturned the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision legalizing safe access to abortion nationwide. Many states will drastically limit access or even ban abortion entirely. Across the U.S., restricting and/or denying access to abortion services will have a disproportionate impact on poor women, girls, and transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) people who are more likely to be Black, Indigenous, or people of color (BIPOC).

We know that this decision will have terrible consequences for our country beyond abortion access. This decision erodes privacy rights. It will increase barriers for people needing abortion services, especially those at the intersections of racism, sexism, and transphobia. Racism, transphobia, and misogyny are intertwined public health crises. Unless we push back, they will result in unacceptable long-term health effects.

While abortion in Washington remains legal despite today’s Supreme Court ruling, the Seattle Office for Civil rights is reviewing how we can strengthen protections for those who choose to terminate their pregnancies. We know that access to abortion is necessary and that true access includes freedom from discrimination and retaliation.

There are historical connections between the modern reproductive rights movement and control over the reproductive health and function of many different communities. It’s critical to understand what reproductive rights are, its history, and how a more inclusive framework known as reproductive justice strives to achieve bodily autonomy across all races and genders.

Introduction to the History of the Reproductive Rights Movement

What we understand to be the reproductive rights movement today began to actively take shape in the early 20th century, focusing first on birth control access.

Margaret Sanger was a reproductive rights pioneer of the early 20th century. She was a public health nurse who opened the first birth control clinic in the U.S in the Brownsville neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York in 1916. Despite being a visionary for women’s rights at the time, Sanger’s contributions are marred by racism. She gave her public support to eugenics. Sanger’s views, however, were not unique.

Eugenics

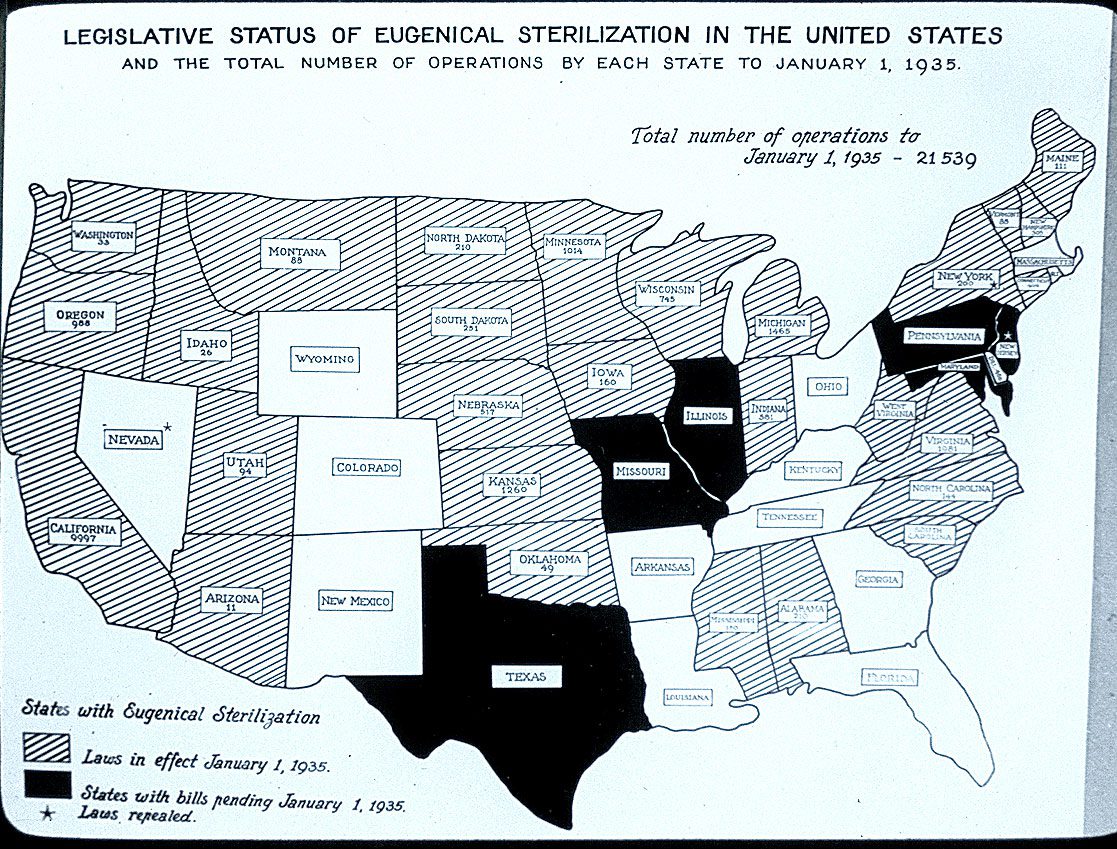

Eugenics is a scientifically inaccurate theory that asserts humans can be improved through selective breeding, justifying the elimination of people considered to be genetically inferior. The American eugenics movement began in the late 1800’s and was rooted in racism, misogyny, classism, and ableism.

Eugenics as a theory and medical philosophy was popular across the political spectrum of the late 19th and early 20th century. In fact, a key factor in the first anti-abortion arguments of the 19th century was that too many white American-born women were ending their pregnancies, “opening the door for the country to be overrun by fertile foreigners.” Doctors of that time also argued that abortions were likely to be fatal and drive women to insanity. Historians, however, note that the procedure was still safer at that time than childbirth.

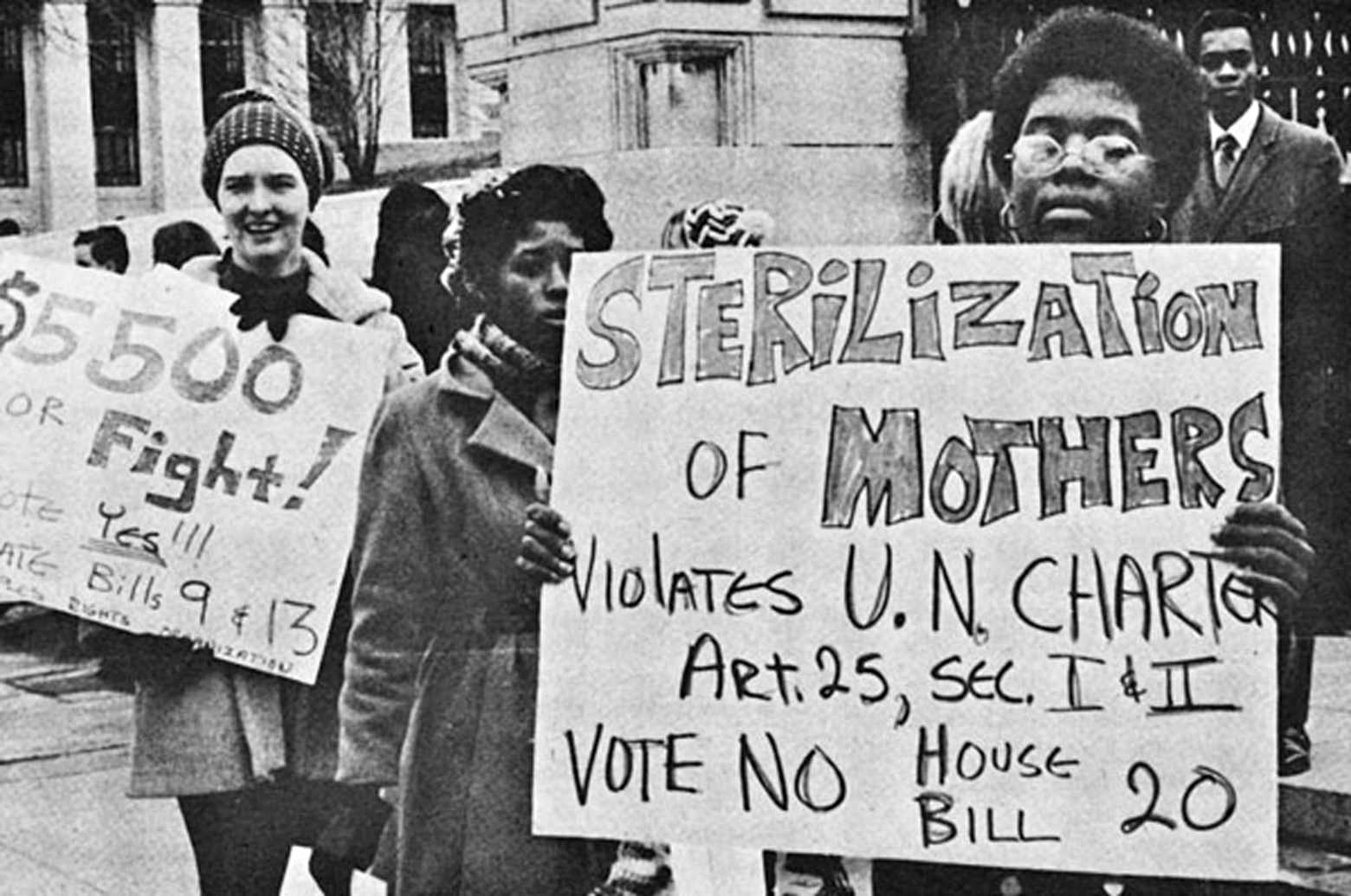

Even as recently as 2020, a nurse working at an Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention center in Georgia came forward with shocking accounts of medical abuse. She claimed that involuntary hysterectomies were performed on detained immigrant women. As horrific and infuriating as these allegations are, it’s important to note that the U.S has previously engaged in forced sterilization campaigns against the poor, disabled, and communities of color. These campaigns were substantiated by eugenics and publicly supported by many.

Since the court ruling on Roe v. Wade in 1973, the reproductive rights movement has focused extensively on preserving the legal right to abortion while putting less emphasis on other needs, including addressing the harms of medical racism like forced sterilization, abortion access, and other healthcare needs for women, girls, and TGNC people impacted by the reproductive rights framework.

Defining Reproductive Justice

SisterSong, a national collective centered on reproductive health for women of color and transgender people, defines Reproductive Justice as a human right to maintain personal bodily autonomy, to have children or not have children, and to parent the children they have in safe and sustainable communities.

Reproductive Justice was first coined in the summer of 1994 by a group of Black women in Chicago. They recognized that the women’s rights movement in the U.S., led by white women, used a much too narrow scope for reproductive rights for all women. Reproductive Justice combines reproductive rights and social justice. It is rooted in an internationally recognized human rights framework created by the United Nations. This is different than the mainstream reproductive rights movement that is rooted in a “pro-choice” framework, or an individual’s constitutional right to privacy.

A major distinction between reproductive rights advocacy and reproductive justice is the notion between access and choice. For example, while pro-choice advocates are focused on legalizing abortion as an individual choice, that is not enough to address systemic realities that many poor women, BIPOC women, and TGNC people face. There are still cost prohibitive barriers and limited or no access to providers that impede the exercise of a meaningful choice.

While those within both movements view abortion access as critical, there is more to reproductive health and autonomy than abortion access. For example, BIPOC women and other marginalized people may also have difficulty accessing contraception, comprehensive sex education, STI prevention and care, alternative birth options, adequate prenatal care, livable wages, and more.

Reproductive Justice also addresses the absence of transgender people and other gender diverse communities in mainstream conversations around reproductive rights; for example, transgender men or non-binary people able to give birth. Historic strategies from the reproductive rights movement were not equipped to address these needs.

Transgender Rights

Positive Women’s Network (PWN) believes reproductive justice can be realized when people of all genders have the economic, social, and political power necessary to make healthy decisions about their bodies, reproductive needs, and sexualities without threat of violence, coercion, stigma, or discrimination.

As mentioned in an earlier post, TGNC people face astounding barriers socially and economically. Further, they are targets of interpersonal and institution violence with increasing exposure if we consider TGNC folks who hold multiple identities including those who are BIPOC, immigrants, sex workers, or living with disabilities. Therefore, if we are to center those most impacted, the needs of TGNC people must be embedded into reproductive justice advocacy.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court’s decision today will cause significant harm to all communities, but most egregiously in communities where race and gender intersect. Abortion access is a critical medical intervention to reach liberation. By analyzing the history of the reproductive rights movement in the U.S., it’s clear that legal abortion access has far-reaching implications as a critical matter beyond privacy rights. When the scope is only narrowly framed as pro-choice and reproductive rights, we sacrifice the dignity and bodily autonomy of communities of color and poor people. This is rooted in our country’s legacy of anti-Black racism, Indigenous erasure, transphobia, and misogyny. Reproductive justice brings a principled lens that refocuses on quality of life that is affirming, uplifting, and supportive of healthy Black and Brown communities.